Harvey Update: Supply, Demand and Gasoline Markets

Mark Green

Posted September 5, 2017

Before then-Hurricane Harvey first made landfall, we discussed how mega-weather events historically have impacted the regional/national oil supply chain and supply levels in the marketplace. The uncertain path of Hurricane Irma will drive continued conversation about storm effects on refineries and other energy infrastructure and the potential for market impacts around the country.

The U.S. Energy Department reports that as of Monday afternoon, eight refineries were shut down, representing a combined capacity of more than 2.1 million barrels per day or about 11 percent of total U.S. capacity. Eight refineries had begun the process of restarting after being shut down, which could take a number of days or weeks to complete.

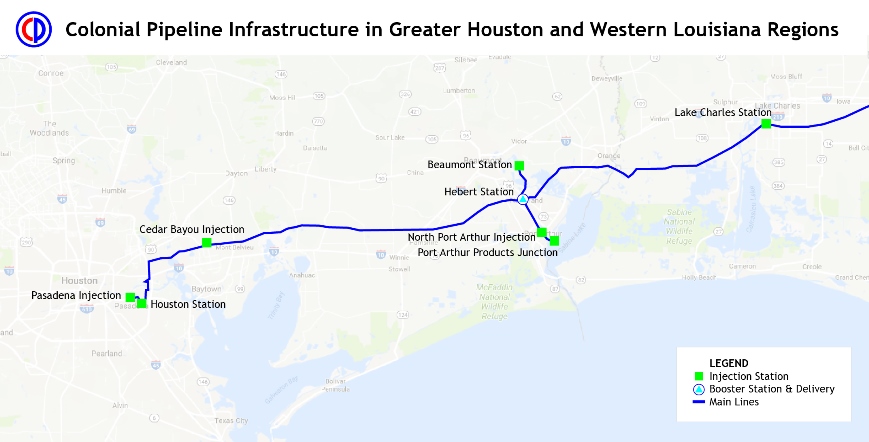

Meanwhile, operators of the Colonial Pipeline, the 5,500-mile pipeline that runs from Houston to Linden, N.J., reported Monday night that its distillate Line 2 had been restarted between Houston and Lake Charles, La., and that its gasoline Line 1 was on schedule to be restarted between those points on Tuesday. The lines had been down or working on a limited basis following Harvey.

The effects of restricted gasoline and diesel production due to refinery impacts, and the resulting limited flow of these products through the pipeline were being felt. The Houston Chronicle reported that fuel supplies were constrained in Houston, Dallas and San Antonio. Nationally, AAA said the average price a gallon of gasoline was $2.648, up from $2.378 a week ago. AAA’s Jeannette Casselano:

“Consumers will see a short-term spike in the coming weeks … but quickly dropping by mid to late September.”

Texas Oil and Gas Association (TXOGA) President Todd Staples urged Texans to return to pre-hurricane buying patterns for the fuel they need. Staples said the Gulf Coast fuel marketplace is being helped by the restoration of refining operations. Fuel from other states and countries is being brought in, he said. Staples:

“Every single Texan can help themselves and their neighbors during this period of recovery by not overbuying fuel. … The flood has impacted all infrastructure sectors from water and electricity to schools, hospitals and fuel. It is important to maintain normal routines and normal buying patterns for fuel to the best of your ability, and to conserve when you can. When we overreact, we put a strain on all of our resources. … All of us can help – not further hinder – recovery by meeting our basic fuel needs until fuel supply chains can replenish.”

As we’ve mentioned in previous posts, the nation’s energy infrastructure system is large and geographically diverse. The Texas-Louisiana area is an important part of that system, yet current inventories of crude oil and refined products nationwide are relatively high and could help offset storm-related supply disruptions, though supply issues could occur if infrastructure constraints restrict access to certain regions. Other transportation modes are helping replenish product supplies, including tanker trucks and river barges. Shipments from overseas also may assist.

It helps to understand how the system is set up, and the other day we shared this interactive graphic showing the various components in the oil supply chain and the way they work together to in a process that starts with energy exploration and ends at consumer outlets:

Oil Supply Chain

(Interactive Content Best Viewed on Large Screens)

Identify

Identify

Modern oil geologists examine surface rocks and terrain, with the additional help of satellite images. However, they also use a variety of other methods to find oil. They can use sensitive gravity meters to measure tiny changes in the Earth’s gravitational field that could indicate flowing oil, as well as sensitive magnetometers to measure tiny changes in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by flowing oil. They can detect the smell of hydrocarbons using sensitive electronic noses called sniffers. Finally, and most commonly, they use seismology, creating shock waves that pass through hidden rock layers and interpreting the waves that are reflected back to the surface.

Explore

Explore

When a prospect has been identified and evaluated and passes an oil company’s selection criteria, an exploration well is drilled in an attempt to conclusively determine the presence or absence of oil or gas. Five geological factors have to be present for a prospect to work and if any of them fail neither oil nor gas will be present:

- A source rock

- Migration

- Trap

- Seal or cap rock

- Reservoir

Hydrocarbon exploration is a high risk investment and risk assessment is paramount for successful exploration portfolio management. Exploration risk is a difficult concept and is usually defined by assigning confidence to the presence of five imperative geological factors, as discussed above.

Design and Construct

Design and Construct

Although there is some variability in the details of well construction because of varying geologic, environmental, and operational settings, the basic practices in constructing a reliable well are similar. The ultimate goal of the well design is to ensure the environmentally sound, safe production of hydrocarbons by containing them inside the well, protecting groundwater resources, isolating the productive formations from other formations, and by proper execution of hydraulic fractures and other stimulation operations.

Produce

Produce

The first step in the oil supply chain is production. During production, crude oil is produced on both land and at sea. Oil production includes drilling, extraction, and recovery of oil from underground.

Transport

Transport

At multiple stages of the oil supply chain process, oil is transported to storage, refineries, terminals, and finally to the point of sale. There are four basic modes of transportation of crude oil from production to the point of sale: trains, trucks, ships, and pipelines.

Storage

Storage

Once the oil has been produced, it is transported to short-term storage. Short-term storage serves as the staging area for crude oil distribution throughout the entire supply chain. Storage facilities allow for adjustments in supply and demand throughout the entire supply chain. The Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) is an emergency fuel storage of crude oil maintained by the United States Department of Energy used to mitigate supply disruptions.

Refine

Refine

Refineries act as the main transformation point for all crude oil into various consumer products. After receiving oil from storage facilities, refineries use various chemical separation and reaction processes to transform crude oil into usable products such as: fuel oil, diesel oil, jet fuel, and multiple essential manufacturing feedstocks.

Feedstocks

Feedstocks

From the refineries, feedstocks are transported to manufacturing facilities where they play a critical part of many manufacturing supply chains, such as medical equipment, plastics, organic chemicals, refined gases, and lubricants.

Terminal

Terminal

Refined fuel that is ready for use is transported to terminals. Terminals are located closer to transportation hubs and are the final staging point for the refined fuel before the point of sale. After entering the terminal ethanols and additives are added to the final refined product before fuel is transported.

Point of Sale

Point of Sale

Once the refined fuel leaves the terminal, it is transported to its final point of sale, which includes fuel stations and airports. Trucking, shipping, and delivery lines provide the final, finished product which can be delivered across the country.

Once crude oil is delivered to the refinery, it is manufactured into gasoline and diesel. (In that vein, the Energy Department has authorized the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to negotiate and execute emergency exchange agreements with three refiners to provide 5.3 million barrels of crude oil.) Refined products are moved from the refinery via pipelines to fuel terminals. When supply is constricted in a given market, product often is moved from a region with excess supply into the market where supply is needed. Historically, fuel prices have increased across the country as product is moved to keep the nation well-supplied with fuel.

Now, it’s also helpful to know some basics about the fuel marketplace and the processes that bring finished consumer products from refineries to retail outlets.

Gasoline, diesel and other fuels are derived from crude oil. Crude is a globally traded commodity, which means its price – while impacted by domestic factors – is set on the world market. As with all commodities, price is set by both current and anticipated future factors impacting supply and demand, including production rates, spare capacity, inventories, economic growth, seasonal changes in demand and many others.

Yet, consumers don’t use crude oil, they use refined products such as gasoline and diesel. As crude is by far the largest economic cost for refiners making gasoline, diesel and other fuels, their prices normally tend to mirror those of crude. Refinery and other infrastructure outages, such as those caused by Harvey and past major storms, can alter the norm. Refinery outages can reduce product available to consumers. Similarly, disruptions in the transportation sector – to pipelines, tankers, barges, trucks and rail – also can temporarily reduce supply to consumers. When supply falls relative to demand, historically there is upward pressure on prices. As supplies return to affected areas – either through facilities being brought back into service or other sources being diverted to affected areas – prices in the past have tended to moderate.

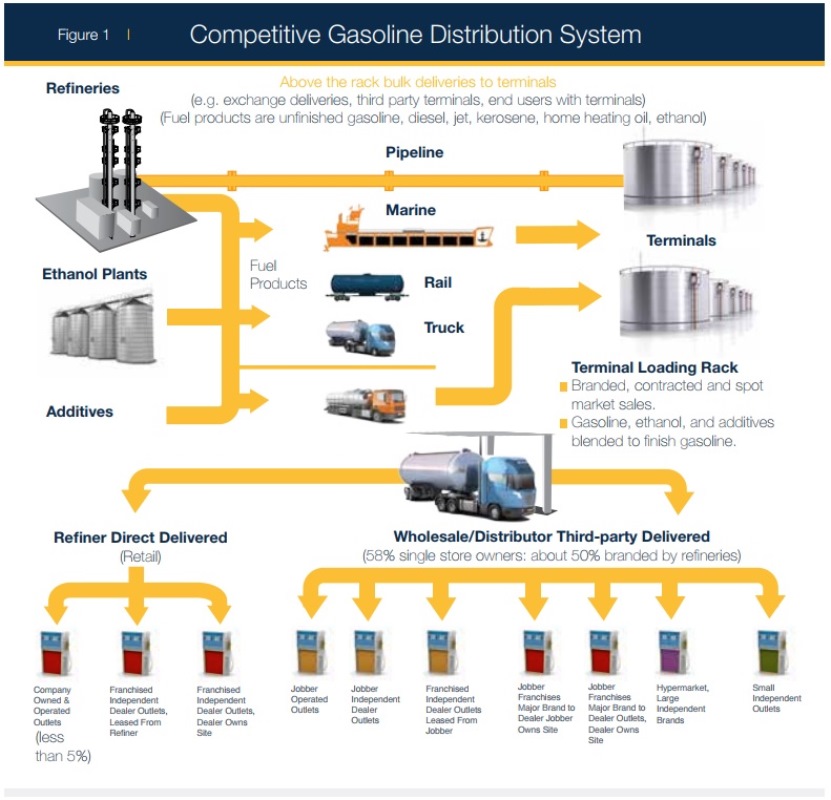

Most refined gasoline is transported by pipeline to fuel terminals, located closer to transportation hubs. Before it goes to retail outlets, this fuel must be blended with ethanol and additives. Blending occurs at the terminal, and then the finished gasoline is loaded onto a tanker truck. Here’s what the distribution system looks like:

In addition to broad supply-and-demand influences, other market factors figure into the price of fuel, including the cost to move product where it’s needed and the cost to store the product before it’s delivered to its final destination. The refiner, the wholesale marketer and retailer may have different information and use different criteria in making their decisions on product price.

Nationally, 97 percent of existing gasoline stations are independently owned. About 50 percent of all stations are branded under a refiner’s brand, and about 60 percent of all gasoline stations are owned by a single store owner. The major oil companies don’t own or manage the product in the tanks at these independent retail locations. Retail outlet owners decide pump prices at their stores, and historically this has been closely linked to the prices they pay at the terminal that was supplied by the refinery. Again, supply and demand is the key factor at each level of the distribution chain.

Additionally, a gasoline station owner has to manage his replacement costs to buy the next tank of fuel, which could be nearly 10,000 gallons. When wholesale prices rise, the station owner must try to ensure that the station’s street prices stay competitive while making sure they have the cash flow to buy the next tank full. Historically, as supplies normalize, prices have tended to normalize, too.

The product supply chain brings efficiency, flexibility and resiliency to the system, which helps with meeting shifting market demand. It’s common for companies to buy, sell or exchange fuel supplies with other companies. This allows the adjustment of supply sources during normal day-to-day operations, as well as in the aftermath of a large event such as a hurricane.

Looking ahead, public policies should support additions and improvements to the nation’s energy infrastructure that help mitigate region-specific circumstances. U.S. consumers and manufacturers will benefit if energy companies are allowed to build and maintain infrastructure networks from coast to coast and border to border that provide access to vital resources.

About The Author

Mark Green joined API after a career in newspaper journalism, including 16 years as national editorial writer for The Oklahoman in the paper’s Washington bureau. Previously, Mark was a reporter, copy editor and sports editor at an assortment of newspapers. He earned his journalism degree from the University of Oklahoma and master’s in journalism and public affairs from American University. He and his wife Pamela have two grown children and six grandchildren.