About 'Peak Oil Demand'

Mark Green

Posted June 21, 2023

People have been projecting “peak oil” since M. King Hubbert came up with modeling in 1956 that showed global oil production would crest between 1965 and 1970. Of course, we now know that the analytics back then didn’t account for the advances in technology and innovation seen in recent decades, and global production has grown more than 60% since 1973.

That may surprise some who imagine a future where we don’t use oil or natural gas – two of the world’s leading sources of energy and projected to provide nearly 50% of it in 2050. No doubt, a number of them have refocused on peak oil production’s cousin, peak oil demand, and view the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Oil 2023 report projections as being the last chapter in global oil use.

Well, not so fast. A few points about IEA’s analysis:

1. IEA only projects a slowing rate of oil demand growth

IEA does not project peak demand or declining demand. Rather, the agency projects a slightly slower rate of demand growth. Look how many times “growth” or “grow” is mentioned in the report’s executive summary:

Our projections assume major oil producers maintain their plans to build up capacity even as demand growth slows. A resulting spare capacity cushion of at least 3.8 mb/d, concentrated in the Middle East, should ensure that world oil markets are adequately supplied throughout our forecast period. … Based on existing policy settings, growth in world oil demand is set to slow markedly during the 2022-28 forecast period as the energy transition advances. While a peak in oil demand is on the horizon, continued increases in petrochemical feedstock and air travel means that overall consumption continues to grow throughout the forecast. We estimate that global oil demand reaches 105.7 mb/d in 2028, up 5.9 mb/d compared with 2022 levels.

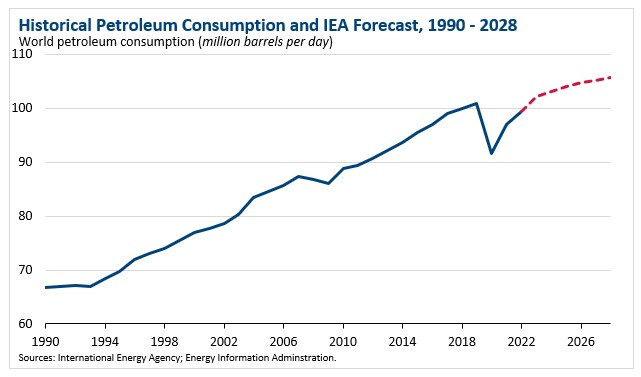

While a slight decline in the demand growth rate is projected, the bigger picture is that IEA also expects demand to reach 105.7 million barrels per day (mbd) in 2028. That’s 6% more than 2022 levels.

The chart above (from IEA data) shows that the slope of the projected growth curve is not significantly different from preceding decades. So, a POLITICO headline trumpeting that IEA sees a “sea change” in oil demand is a gratuitous exaggeration.

2. Exercise caution with projections

IEA projects oil demand growth this year will be 2.4 mbd, and that growth will decline to 0.4 mbd by 2028. That compares with the 30-year average growth of about 1.1 mbd, year on year. The 2028 number has been the focus of some news coverage, but you have to consider projections with some care. In June 2022, IEA said that 2023 oil demand growth would be 2.2 mbd, then in March the agency said it would be 2.0 mbd, and now it’s back up to 2.4 mbd. There could be any number of reasons for this, such as quickly shifting market factors, but it’s understandable that changes in projections raise questions about a forecast five years away.

Meanwhile, perhaps IEA is overly optimistic about the combined ability of electric vehicle (EV) sales and vehicle efficiency improvements to reduce oil demand by 7.8 mbd between now and 2028. That’s a lot of reduced demand in just five years. As this piece points out, Norway’s annual oil consumption has remained about the same for the past 20 to 30 years – even though virtually all of the country’s electricity comes from hydropower and renewables, and even though 90% of its new vehicle sales are full battery electric or plug-in hybrids. On EVs, IEA projects they will account for 25% of new vehicles sold globally by 2028. While that could happen, it would be nearly double the 14% global EV share in 2022.

3. U.S. oil production could dominate new supply growth

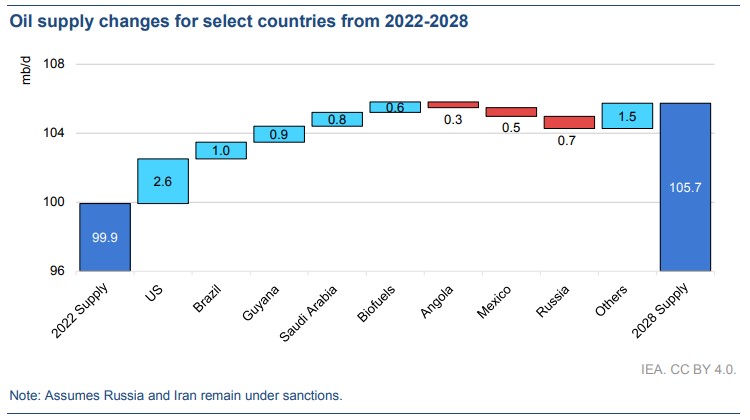

On the supply side – again, IEA is projecting global oil demand will grow to nearly 106 mbd in 2028 – IEA expects the U.S. will lead in production to meet that demand. Seen in IEA’s chart, the agency projects that American production growth from 2022-2028 will be 2.6 mbd – equal to the net production growth of the major producers named below:

Let’s add that IEA projects U.S. upstream emissions will decrease 40%, even as production increases 13% over the time period. Indeed, we know that average methane emissions intensity declined by 66% across all seven major producing regions from 2011 to 2021 – a period of rapid production growth – according to EPA and other government data.

Certainly, the turning point in oil demand that some hope for, even before it’s certain that discarding oil and natural gas is good for modern societies, is unicorn-like. It’s regularly pointed to but never quite realized.

When you look at it, the bend in IEA’s demand growth is gradual and is based on some assumptions that are far from certain – including relatively low global economic growth, a huge uptick in EV sales and the adoption of aggressive energy policies by the world. Dustin Meyer, API vice president of Economics, Policy and Regulatory Affairs:

“The bigger takeaway from IEA’s report is that even if all of what it projects happens, crude oil demand still could increase in a way that is pretty consistent with the historical trend. That new demand means additional supply needs to come from somewhere, and IEA believes the U.S. will produce more of it than any other single country. In the end, this report is actually about the resilience of demand for the reliable, affordable energy provided by natural gas and oil.”

About The Author

Mark Green joined API after a career in newspaper journalism, including 16 years as national editorial writer for The Oklahoman in the paper’s Washington bureau. Previously, Mark was a reporter, copy editor and sports editor at an assortment of newspapers. He earned his journalism degree from the University of Oklahoma and master’s in journalism and public affairs from American University. He and his wife Pamela have two grown children and six grandchildren.