Maryland: Energy to Triumph Over Adversity

Mark Green

Posted October 5, 2017

We’re a hardy lot, we humans, often displaying enormous determination to keep moving forward in the face of steep challenges. Paratriathlete Allysa Seely, though, takes determination to another level entirely.

Seely made history last year by winning a gold medal for Team USA at the summer Paralympics. Eight years earlier she lost her left leg below the knee after surgeries and associated complications in the course of treatment for three separate disorders, two involving her brain. (Read more about it in this interview with ESPN.) She refused to stay down – and energy supported her steely resolve.

Seely ran, swam and biked her way through to win the women’s paratriathlon. She told ESPN:

“I think there's still a big stigma around disability, especially disabled sports. A lot of times people confuse the Paralympics with the Special Olympics. You just don't sign up to go to the Paralympics. You have to qualify just like Olympians do, and it takes years of training and hard work to get to that level. … I train seven days a week. I train two to three times a day and lift in the gym three times a week. I swim almost every day and then bike and run four to five days a week. I'm training 15 to 35 hours a week. It's definitely a full-time job, because I don't want to be outworked.”

Seely is one of about 2 million U.S. residents living life after losing a limb, according to the Amputee Coalition – many with the help of prosthetics that harness the power of energy to provide mobility, capability and, yes, even gold medal-winning athleticism. Maryland, through its nationally ranked medical research centers, helps lead the way.

Putting One Foot in Front of the Other

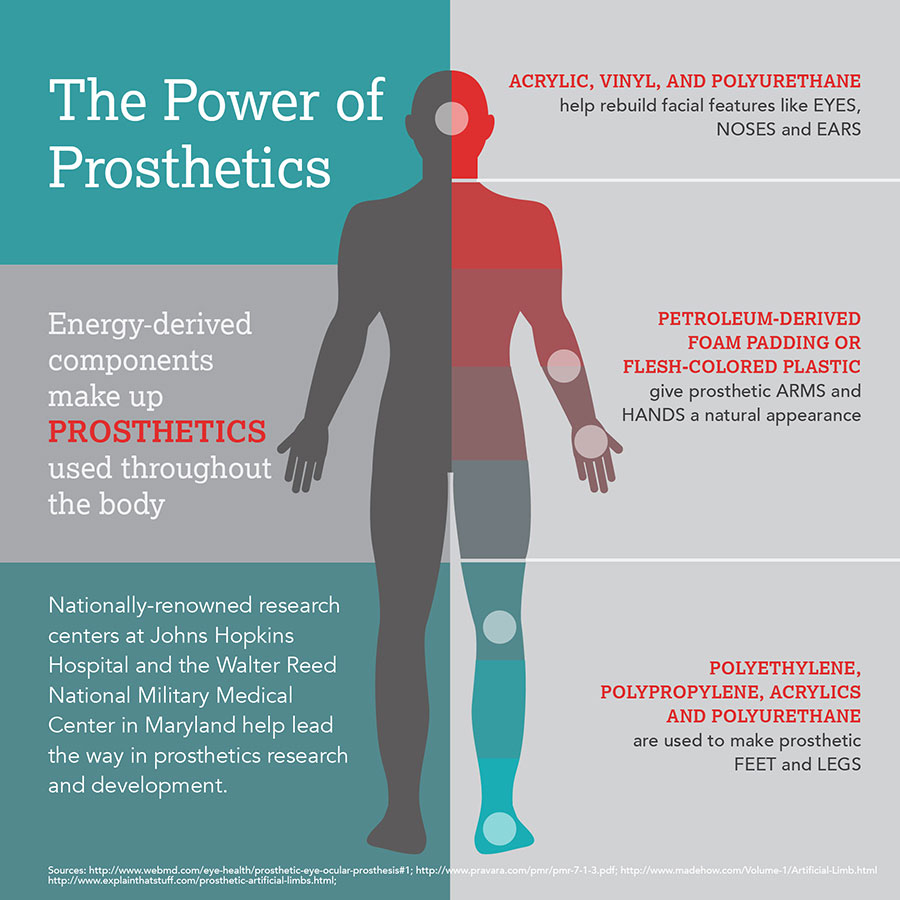

Prosthetics consist of several interconnected parts. Often, they start with the internal structure (also called a pylon), usually made with carbon fiber and covered with petroleum-derived foam padding or flesh-colored plastic.

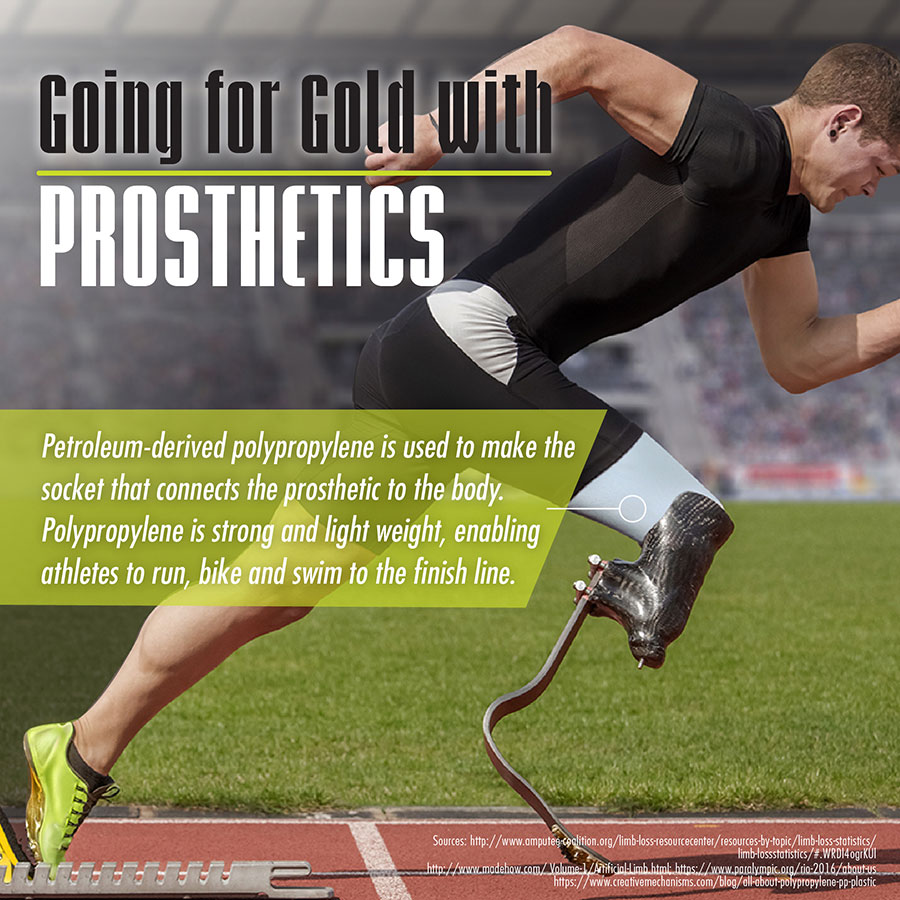

Next, there is the socket, connecting the remaining portion of the limb to the prosthetic. Typically, the socket is made from polypropylene, a thermoplastic durable enough to support body weight with a high elasticity that makes it optimal for custom fitting and mobility.

Many prosthetic legs require feet, both to create a more natural appearance and to increase stability and mobility. These are made from rubber, urethane foam or plastics such as polyethylene, polypropylene, acrylics and polyurethane.

Increasing Mobility Through the Ages

From the ancient Egyptians, to World War I, to the modern tech age, each century has seen important advancements in prosthetics. Today, petroleum-derived materials have enabled prosthetics to be stronger and more lightweight than their earlier equivalents made of wood and iron.

The weight of a prosthetic limb is a crucial factor. It’s not something most people think of, but a person’s two legs are about 30 to 40 percent of their total body weight, and their two arms about 10 percent. A prosthetic limb must be much lighter. To create these lightweight components, petroleum-based plastics are used. These plastics are not rejected by the human body and are strong enough to perform well for years.

The Old Line State Blazes the Trail

In 2013, a total of 3,053 medically advised amputations were performed at hospitals in Maryland, making prosthetic research and development a top priority for the state.

At the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, one of the nation's premier military medical facilities, and Johns Hopkins Hospital, a top-ranked hospital and biomedical research center, professionals offer a full range of prosthetic services using cutting-edge technology. In addition, the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory is revolutionizing prosthetics by creating an artificial limb controlled through the mind.

Facing Adversity Head-on

In addition to limbs, petroleum-based prosthetics also are used in facial reconstruction. Not only do these prosthetics rebuild noses, ears and other facial features, but they also rebuild self-confidence in those that use them. Typically, facial prosthetics are made using silicone elastomers as well as petroleum-derived acrylic resins and co-polymers, vinyl and polyurethane.

There also are ocular prosthetics for those who have lost eyes. Though historically prosthetic eyes were made with glass, today they’re commonly made from acrylic, a polymer constructed from petroleum distillates.

Prosthetics made from petroleum-derived products are defying limitations for those who lose facial features and for the 507 people who lose a limb every single day. Because of the energy used to make prosthetics, activities ranging from the most routine – a walk to the mailbox or a reach for a coffee cup in the cabinet – to the most extraordinary – running and jumping or swinging and kicking – are more accessible than ever before. Seely is running, swimming and biking proof. For her, a world-class athlete, it’s about overcoming, adjusting and striving higher and higher:

“Over time, as I've gotten more fit, my leg has gotten smaller, and we had to make new prosthetic legs. It's something you have to get used to, it changes. Obviously, at a race you want to be able to trust in it 100 percent, you want to know how it's going to react and respond, so when you have to change some of them it can become a little shaky. But at the same time prosthetics have come so far. I tell little kids who have never seen a prosthetic that I can do everything that I could do before, so that's something that I'm really grateful for.”

About The Author

Mark Green joined API after a career in newspaper journalism, including 16 years as national editorial writer for The Oklahoman in the paper’s Washington bureau. Previously, Mark was a reporter, copy editor and sports editor at an assortment of newspapers. He earned his journalism degree from the University of Oklahoma and master’s in journalism and public affairs from American University. He and his wife Pamela have two grown children and six grandchildren.